by Michelle Ann Kratts

April 2012

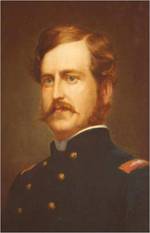

Photograph of a portrait of Peter A. Porter, courtesy Peter B. CoffinThere is something else about Niagara…beyond the great cascade of water and the daredevils and the lovers that inevitably come to celebrate at her altar. Something that overcomes us and swallows us whole. Something that makes us attempt the unthinkable. We stand at the edge and in those frantic skips of our heart we know what it is: poetry.

Photograph of a portrait of Peter A. Porter, courtesy Peter B. CoffinThere is something else about Niagara…beyond the great cascade of water and the daredevils and the lovers that inevitably come to celebrate at her altar. Something that overcomes us and swallows us whole. Something that makes us attempt the unthinkable. We stand at the edge and in those frantic skips of our heart we know what it is: poetry.

Poetry is a lot of things. Maybe it’s a rhyme for you. Maybe it’s something caught beneath your breath and then it’s gone forever. It may be a smudge from a little hand on a window. Or the last time you saw your father. It could be a mirror. Or something endless and beautiful like water.

One of Niagara’s first native poets was Peter A. Porter. He is most well known as “the colonel”—as opposed to his father, who was “the general”. He died a hero on a battlefield in Cold Harbor, Virginia, on June 3, 1864. Five men crawled upon their bellies in the stench and heat of that southern battlefield to retrieve his body. It rained on them and they said that the rain brought on a vaporous steam that made it all the more unbearable. They tied a cord to his sword belt and dragged him over the damp and bloody clay until they reached Union lines. Peter’s sister, Elizabeth, who was serving as a nurse in Baltimore, brought her brother’s body back to Niagara Falls—for services at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church (of which their father was the founding member) and on to Oakwood Cemetery (where Peter was a trustee) for burial.

Often sandwiched in between his father and his son, Colonel Peter A. Porter, is usually mentioned merely as a footnote to their more “interesting” and “longer” lives…until now. Little by little I have been accumulating bits and pieces of a man who was much more than a father and a son and a soldier. And interestingly enough it has come to me through his poetry.

Apparently, Peter (whom we won’t refer to as “colonel” anymore for the purposes of this sketch) never wanted to be a military man. Born in Black Rock (Buffalo) on July 14, 1827, he came to Niagara Falls with his father and his sister. His mother, Letitia, had died when he was only four years old. He studied at Harvard and then at the universities of Heidelberg, Berlin and Breslau. He returned to Niagara in 1852 but probably not without bringing some of that revolutionary fervor that had swept through Europe while he was abroad back home with him. In fact, it was said that his home (razed in the 1930’s) --which had been quite unusually built with German plans-- was the equivalent of a European style salon—complete with interesting guests and lively conversation. It was the heart of all culture in Niagara Falls. He brought his new wife, the love of his life, Kentucky-born, Mary Breckinridge, and their newborn son, Peter, to live in this magnificent house on Buffalo Avenue. It was located between the area that is now the ghost yards of the Shredded Wheat plant and the Niagara River. Sadly, Mary died a young woman in just two years during the terrible cholera epidemic that swept through the country. Peter, despondent and out of his mind with grief, buried her in Oakwood Cemetery and then ran off once again to Europe in order to heal his fledgling soul. He returned a few years later, refreshed, and married another southerner, Josephine Morris—who would outlive him and raise his son, Peter, as her own.

From “A Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812,” by Benson J. Lossing, 1868 He credits this drawing to Peter A. Porter. It was during this time that it is possible that Peter and his sister, Elizabeth, may have spent much of their time working at their “secret charities.” Today the evidence increasingly points to the possibility that they were in fact the mysterious leaders of the Underground Railroad in Niagara Falls. We are not sure about the details as he was an uncommonly modest and humble man. Quiet and resigned he was constantly avoiding any acknowledgement of his deeds. We do know that it was not uncommon for him to act selflessly. In fact, when the War of the Rebellion first broke, he consistently turned down offers to lead a regiment—preferring instead to sign up as a private. He held glamorous parties at his home and allowed every manner of man from his regiment to join in the fun. Finally as the war raged, it was inevitable…and he took on the 8th New York Artillery. Even then, while he was off serving with his regiment in Baltimore, he was offered the chance to leave the military life and serve as Secretary of State of New York. Perhaps it was that moment—when that split second decision was made—that sealed his fate and won the men in his regiment over.

From “A Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812,” by Benson J. Lossing, 1868 He credits this drawing to Peter A. Porter. It was during this time that it is possible that Peter and his sister, Elizabeth, may have spent much of their time working at their “secret charities.” Today the evidence increasingly points to the possibility that they were in fact the mysterious leaders of the Underground Railroad in Niagara Falls. We are not sure about the details as he was an uncommonly modest and humble man. Quiet and resigned he was constantly avoiding any acknowledgement of his deeds. We do know that it was not uncommon for him to act selflessly. In fact, when the War of the Rebellion first broke, he consistently turned down offers to lead a regiment—preferring instead to sign up as a private. He held glamorous parties at his home and allowed every manner of man from his regiment to join in the fun. Finally as the war raged, it was inevitable…and he took on the 8th New York Artillery. Even then, while he was off serving with his regiment in Baltimore, he was offered the chance to leave the military life and serve as Secretary of State of New York. Perhaps it was that moment—when that split second decision was made—that sealed his fate and won the men in his regiment over.

“I left home in command of a regiment mainly composed of the sons of friends and neighbors committed to my care. I can hardly ask for my discharge while theirs cannot be granted; and I have a strong desire, if alive, to carry back those whom the chances of time and war shall permit to be present, and to account in person for all…”

It was the uncanny beauty and humanitarianism of his words that gave Peter such an esteemed place in our history. We can infer much about the man by his actions, but we can get inside his soul because of the poetry of his words. Not one of his men forgot these words. They memorized them and recalled them in their moments of weakness and in the end they carried him back to Niagara Falls.

But what of his words, his poetry? He never purposely published his poetry so it has been extremely difficult to find his work. Some pieces were discovered in some of the most prominent literary journals of his day (Harpers Monthly, Putnam’s Journal and the Crayon)—published anonymously. There are five poems that we are aware of at this point and I keep them in a binder in our Robert F. Barthel and Loraine L. Baxter Niagara Poetry Collection at the Lewiston Public Library. You are more than welcome to read his poetry along with the poetry of other Niagara area poets located in our Local History Room—just ask to have the cabinets opened and you will be surprised at what you find.

The first, the mysterious, “Come Nearer to me, Sister,” is my favorite. Apparently written around February of 1845, it was published posthumously in the Commercial Advertiser, Buffalo, on November 19, 1864. The kind historians at the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society found the original and Larry Steele, the administrator at Oakwood Cemetery, made a copy and picked it up for me one day last year. I could hardly contain my excitement when he made that special delivery. What makes this poem so unusual is that it was actually mentioned in the Memoir of Elizabeth T. Read—a young girl who died on January 20, 1847, at the Institution of the Messrs. Abbott, in New York City. The young girl was “particularly interested in all pieces of poetry which had reference to death, and to scenes of the future world.” It was said that a few weeks before her death she wrote to her sister that she “had met with a beautiful piece of poetry, which she copied for her sister’s perusal.” It is unknown how Miss Read came in contact with this beautiful and tragic poem almost twenty years before it was published, however, it is possible that she had been an associate of Peter’s sister, Elizabeth, who also went to school in New York City (at Madame Conda’s). Perhaps this touching testament to Elizabeth (Peter’s sister) was shared amongst the school girls. I imagine Elizabeth was utterly moved by the genuine romanticism of the death imagery and by the prominent place he held for her in this tragic moment. Here he is, just a teenager, with thoughts of death still raw (their father had died the previous year) imagining his own death—his sister at his side. Ironically, it was as if he saw into the future, for it was Elizabeth who would bring his body back to Niagara Falls. It’s possible that Elizabeth may have been instrumental in publishing this in the Commercial Advertiser back in November of 1864. He was so newly gone, and her heart must have been aching for him. They were very close throughout their lives and maybe even more soul mates than kin. The poem is sad and fleeting and full of memories of youth and promises after death. He even mentions their cousin, Mary, his future wife, and how although they were not married yet their “wedlock’s golden thread will run through eternity.” He writes how he hopes she will find someone kindly but “in the world above” he would “claim her as” his “own…” “Come Nearer to me, Sister,” is definitely the most romantic of the poetry we have found.

Another poem, the dreamy, “Arcadia, A Medley,” was published in Putnam’s Journal in May of 1857. Peter’s friends from New York’s famous Century Club insisted upon publishing it after he had presented it at their monthly meeting. I can’t help but wonder about this one. Knowing now of the possibilities of Peter’s work on the Underground Railroad, it’s difficult not to read this as something more than what it seems. On the exterior, it’s about an auctioneer selling off a painting of a mythical land known as Arcadia. “Going…going…gone!” Of course, the image of the auctioneer (when viewed from this perspective) could reveal the “slave auctioneer.” And the whole idea of “Arcadia, A Medley,” a journey to the Promised Land “that weary souls have sighed for…this the land heroic hearts have died for…,” could also lead the reader to think of the journey of the runaway slave. He uses literary devices to map out the trip to Arcadia and even states that “here surveyors trace the way of heavenly railroads, that will pay Ethereal dividends…” Maybe I have a little too much of the “conspiracy theorist” about me, but I invite you to have a look and tell me what you think this “Arcadia, A Medley,” is all about. Maybe it is a secret code to one of the most amazing networks in American history. Or perhaps it is just a poem…

Another poem, the dreamy, “Arcadia, A Medley,” was published in Putnam’s Journal in May of 1857. Peter’s friends from New York’s famous Century Club insisted upon publishing it after he had presented it at their monthly meeting. I can’t help but wonder about this one. Knowing now of the possibilities of Peter’s work on the Underground Railroad, it’s difficult not to read this as something more than what it seems. On the exterior, it’s about an auctioneer selling off a painting of a mythical land known as Arcadia. “Going…going…gone!” Of course, the image of the auctioneer (when viewed from this perspective) could reveal the “slave auctioneer.” And the whole idea of “Arcadia, A Medley,” a journey to the Promised Land “that weary souls have sighed for…this the land heroic hearts have died for…,” could also lead the reader to think of the journey of the runaway slave. He uses literary devices to map out the trip to Arcadia and even states that “here surveyors trace the way of heavenly railroads, that will pay Ethereal dividends…” Maybe I have a little too much of the “conspiracy theorist” about me, but I invite you to have a look and tell me what you think this “Arcadia, A Medley,” is all about. Maybe it is a secret code to one of the most amazing networks in American history. Or perhaps it is just a poem…

A more humorous piece was published in The Crayon in February of 1859—again by Peter’s friends from the Century Club. Thanks to the archivist at New York’s Century Club, we have some notes from the special occasion in which, “The Centurion’s Dream,” appeared. Because of the fact that “so many hearers” during the Twelfth Night Festival at the Century Club were “delighted with the sprightly humor, the playful turn of the rhyme and the fanciful allusions” and had requested their own copy it became necessary to have “The Centurion’s Dream,” in print. I love how the editor of The Crayon couldn’t help but compare “the modest author” to Niagara, itself, when he insists that “the iridescent hues of the poem were not caught from the spray of Niagara, but from the soberer colors of a well stocked library… and Mr. Peter A. Porter.” This one is a dream and contains numerous allusions to literary masterpieces. It is put together as a sort of literary potpourri (which he calls “an ollapodrida). It’s quite fun to read aloud.

A more humorous piece was published in The Crayon in February of 1859—again by Peter’s friends from the Century Club. Thanks to the archivist at New York’s Century Club, we have some notes from the special occasion in which, “The Centurion’s Dream,” appeared. Because of the fact that “so many hearers” during the Twelfth Night Festival at the Century Club were “delighted with the sprightly humor, the playful turn of the rhyme and the fanciful allusions” and had requested their own copy it became necessary to have “The Centurion’s Dream,” in print. I love how the editor of The Crayon couldn’t help but compare “the modest author” to Niagara, itself, when he insists that “the iridescent hues of the poem were not caught from the spray of Niagara, but from the soberer colors of a well stocked library… and Mr. Peter A. Porter.” This one is a dream and contains numerous allusions to literary masterpieces. It is put together as a sort of literary potpourri (which he calls “an ollapodrida). It’s quite fun to read aloud.

Two other poems are frequently attributed to Peter A. Porter: “Lines in a Young Ladies Album” and “On the Early Death of Mr. George S. Emerson.” “Lines in a Young Ladies Album” was written to accompany drawings Peter scribbled into a young relative’s album. The drawings included a likeness of the Falls with Father Hennepin, LaSalle and an Indian Chief in the foreground…”the chief, the soldier of the sword, the soldier of the cross…one died in battle, one in bed and one by secret foe…but let the waters fall as once they fell two hundred years ago.” “Lines in a Young Ladies Album” is particularly beautiful and moving to those of us who know Niagara most intimately. On July 31, 2011, Niagara Falls historian, Paul Gromosiak and Niagara Falls Public Library director, Michelle Petrazzoulo, took turns reading the lines of this poem at the opening reception of the Robert F. Barthel and Loraine L. Baxter Niagara Poetry Collection at the Lewiston Public Library.

“On the Early Death of Mr. George S. Emerson” was often used as an accompaniment to Peter’s own obituary, however, he wrote it, himself, many years before upon hearing of the death of a young friend. This poignant elegy reveals, once again, Peter’s preoccupation with premature death and that glorious meeting in heaven. “Perchance we meet on heaven’s eternal shore…”

During the month of April we celebrate poetry and inevitably that leads me to think of one of my favorite Niagara poets, Peter A. Porter. Hopefully, with time, other poems will reveal themselves and ultimately allow us a more complete picture of one of Niagara’s most fascinating men.