Michelle A. Kratts

It was probably on the morning of April 15th when she first heard the horrible news. From her glamorous apartment in The Lochiel, located on Buffalo Avenue and 3rd, well within the roar of Niagara, Mrs. Emily S. Douton must have been in a state of shock. The newspapers had run the startling story: the White Star Liner, Olympia, reports the Titanic has called “C.Q.D.” to the Marconi wireless station at Camp Race in Newfoundland. The ship has struck an iceberg on her maiden voyage and immediate assistance is being requested. It was all a miserable dream, perhaps. Yes, Mr. Douton was indeed on his way back to New York, but perhaps plans had changed yet again. He was meant to be on the Olympia. He was meant to leave on March 27th. Perhaps he wasn’t on board the Titanic after all. Perhaps, the ship was still afloat, or perhaps he was on one of the passengers removed and safe on board another vessel--a warm cup of tea in his hands at this very moment. Perhaps, perhaps.

Mrs. Emily S. Douton, a native of England, was not the sort of woman who enjoyed living with “perhaps.” Intelligent and calculating, she was the local representative and national organizer of the National Protective Legion—an insurance company. She was prepared for all manner of things—for certainly life is known to throw in some surprises. Of course, she knew this more than anyone as she poured over her daily work. It was the business of death, accident and disability claims that filled her hours. How could it be that she would be thrown into that miserable mess? She was meant to be on the other side of the desk. But this was reality and this was the undeniable case—Mrs. Emily S. Douton, 46 years old, resident of Niagara Falls, New York, was about to become inextricably involved with one of the worst disasters in the world’s history.

As the days passed and the horrific details came rushing in by wire, family members were notified. There were accounts of women losing their minds with grief—such as Mrs. Stanley Fox of Rochester.

But Emily, though heartsick, was not to lose her mind. She was to keep calm and to carry on hope that he was still alive. The newspapers in Niagara Falls, Buffalo, Rochester and in Holley carried the harrowing updates on Mr. Douton’s fate. The news was nothing but grim. His trip was meant to be a pleasant one. He had been abroad since November replenishing his poor health and visiting his old home in England for the first time since he had come to America. He had been travelling with Miss Lillian Bentham and Peter Mackain—both close family friends from Rochester.

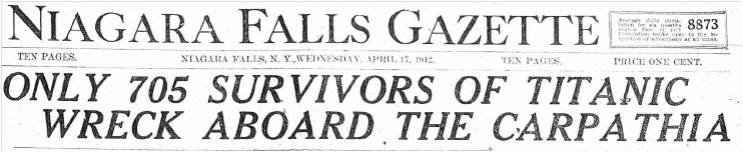

It was once Emily had collected herself that she found that she must immediately go to the home of Mrs. Bentham to await any news. It was said that the women and children were saved first and Miss Bentham’s name was on the list released of survivors on board the Carpathia. William Douton’s name was not on the list. She scoured the list. Hoping for the chance of a mistake, a misspelling, a hasty scribbler who left him out by accident. But nothing. By April 18th, she gathered her daughters, Mrs. Charles Cooper and Mrs. Epke, and they left for New York at midnight. She would be there when the Carpathia rolled in. She would gather Miss Bentham and find out the fate of her own husband.

The moment arrived late on Thursday evening as the Carpathia reached her dock. It was said that the “saddest scene was the eager watching of the disembarking throng of survivors by relatives of those reported missing, in the vain hope that there might have been some mistake or omission in the names and that their own loved ones might after all be among the saved…and the sorrow-stricken faces as this last frail hope faded and died…” Such was the case for Mrs. Douton and her daughters. Mr. Douton was not among the survivors. Their meeting with Lillian was bittersweet for it was then that they finally learned of the fate of husband and father.

The Holley Standard reveals a touching portrayal of this historic moment as Lillian was “met at the dock by Mrs. Douton.” Lillian was the only survivor from Holley and although “suffering severely from the physical hardship and nervous shock of her experiences she was in better condition than had been feared and was able to relate of the most thrilled recitals of experiences given by any of the survivors…” It was published on April 25, 1912, in the Holley Standard. The story is gruesome in its details. She describes every moment and tells the stories of the dead being “thrown overboard,” of “officers with pistols” and “scenes on the deck,” as well as the fate of Mr. Douton…

Lillian had already retired in her cabin when she was thrown from the side of the bed and clear across the stateroom. Her roommate was an old lady and was also thrown out of her bed. She heard a lot of running outside her door and found a boy of the steward’s force and he merely answered that the ship had hit a fisherman’s boat. But then after a few more moments there was much alarm and shouting and it became apparent to Lillian that it was more than a slight collision with a “fisherman’s boat.” Words such as “life boats” were thrown about and that was when she got up and dressed herself and went on deck where “the scene was an awful one” that she would never be able to “get out” of her mind. It was at this time that she ran back and proceeded to pound upon her traveling companion and chaperone, Mr. Douton’s, stateroom door. Screaming and yelling she waited for him to answer. But there was no answer. It was presumed that he was sleeping when he went “down with the ship.” Or perhaps had been injured and left unconscious from the original jolt with the iceberg. Perhaps….

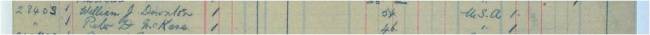

And then all of the puzzle pieces began to fall into place and the nightmare was made more complete. The body of an “F. Dutton” was recovered by the morgue ship Mackay-Bennett and Mrs. Douton was quite certain it was her own “W. J. Douton.” There was no other “Dutton” on the passenger record.

She remarked to the Niagara Falls Gazette that she had gone over the lists over and over again and she knew that F. Dutton was none other than “W.J. Douton,” her husband. For there were so many wireless reports of names that had been wrong and corrections had already been sent out. While in New York she spoke with the officials of the White Star Line who were quite convinced he had gone down with the ship. Emily decided she would wire her brother, a Boston architect, JEL Miller, to meet the morgue ship at Halifax. “Mr. Miller can establish the identification beyond any doubt.”

Identifying the bodies was not for the weak of heart. Unfortunately, Mr. Douton’s body was not identifiable and Mr. Miller left the scene empty-handed. Not unlike many other victims of the Titanic, he may have been lost at sea. On May 9, 1912, his name appeared on the final list of those lost. The Holley Lodge No. 42 IOOF (the Independent Order of Odd Fellows) has often honored the memories of both William Douton and Peter MacKain at Hillside Cemetery in Holley. Both men were members. Mr. Douton had served as noble grand at one time.

Mrs. Douton was probably never quite satisfied with the questionable ending of her husband. How could such a spectacular death on board the Titanic properly register itself in her mind? She went on with her life—the frozen iceberg always in the perimeter of her day’s events. She married again to Charles B. Hyde—well known in Niagara Falls for his work in the paper making business. He left his estate to his beloved wife, Emily, and upon her death she left it to the city of Niagara Falls to be used in the purchase of park property that would bear the name, “Hyde Park.” Emily married also married Dr. A. F. Biondi and died only about one year following her marriage. She died on June 30th, 1923, of cancer of the stomach. She was at her daughter’s home at Hilton, New York. Her body was returned to Niagara Falls where she was buried in Oakwood Mausoleum beside her second husband, Charles B. Hyde and Niagara’s Hyde Park was born from her death. Most women are buried beside their first husbands, but Emily (Douton) Hyde-Biondi’s family was not prepared to send her off with their father and into the frozen sea.

Emily S. (Miller) Douton Hyde Biondi’s final resting place in a crypt in Oakwood’s Mausoleum

Emily S. (Miller) Douton Hyde Biondi’s final resting place in a crypt in Oakwood’s Mausoleum